The Northeast Maglev

Public Service or White Elephant?

Japanese Innovation

For decades, city planners have seen the future of public transportation in maglev trains – “maglev” being short for magnetic levitation. Instead of conventional steel railroad track, maglev trains glide above the track, making for a faster and smoother ride. Since the 1980s, short test tracks have been built in Japan, China, Germany, South Korea, and England, though few have survived to the present day (1).

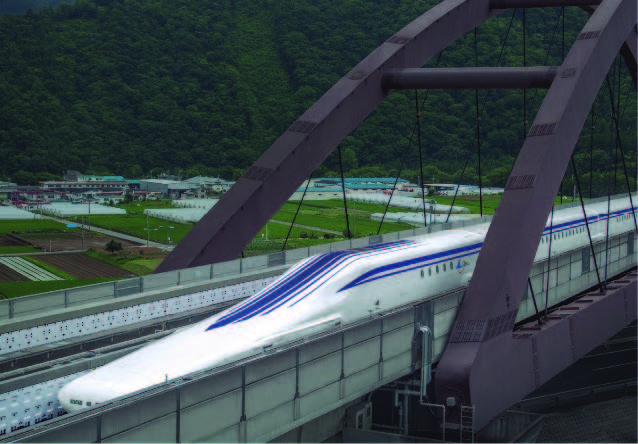

However, Japan – in particular, the Central Japan Railway Company, or JR Central – has pushed ahead with its maglev technology. In 1990, JR Central began construction on a test line in Yamanashi Prefecture, and began extensive testing on an 18.4 km (11.4 mile) section in 1997. By 2013, the line was extended, and JR Central began offering test rides to select members of the public the following year. This test track allowed for speeds of 500 kph (311 mph), fast enough to travel from Tokyo to Osaka in 48 minutes.(2)

The maglev in Yamanashi. Image credit: CNBC

To establish itself as a world leader in railway technology, Japan looked to export their newly-matured system. The United States seemed to be the perfect market, though it would be a tough nut to crack.

American Stagnation

The U.S. is unique in its approach to mass transit. Due to its more spread-out nature, planes are the preferred method of travelling from city to city, even with all of the inconveniences of modern air travel. One place that isn’t spread out, however, is the Northeast Corridor, an area stretching from Boston to Washington, D.C. Here, 17% of the country’s population lives in an area that makes up 2% of its land. Highways in the area are struggling to handle the growing traffic capacity, with traffic congestion increasing 24% in the major NEC cities from 1990 to 2007 (3). Worse, America’s rail infrastructure is over a century old. Government, at both the federal and local levels, is reluctant – even loathe – to spend enough to bring it up to the standards of other world powers - as evident in 2003, when the Maryland State Senate cut off all funding to the previous Baltimore/Washington maglev project.

On this map, traffic congestion is measured by number of hours of delay per commuter. The worst-hit cities are shown in big red pins, and there is a sprawling line of red pins across the Northeast Corridor.

There is only one high-speed rail service in the United States, the Acela Express, which takes passengers across the Northeast Corridor at speeds up to 150 mph (1). High-speed lines throughout the rest of the country are logistically and financially impractical. Amtrak, the U.S. federal rail operator, borrows the majority of its track from freight lines, who naturally give their trains higher priority than Amtrak’s. The only alternative to upgrading the current tracks for high-speed service would be to build new track, which would take on nearly-insurmountable economic, environmental, and legal challenges.

Not to be deterred, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe became personally involved in selling the maglev to the U.S., meeting directly with then-President Obama to license the maglev technology to the U.S. for free for the first 40-mile section – Washington D.C. to Baltimore. If successful, the line would extend northward to New York (1).

A promotional rendering of the SCMaglev. Image credit: SCMaglev/TNEM

Unlike the failed first attempt to bring the maglev to D.C., the new effort would be entirely backed by a private company, The Northeast Maglev, headed by CEO Wayne Rodgers. TNEM raised capital from JR Central, the Federal Railroad Administration, and the state of Maryland to fund its first round of impact studies. In 2015, the project scored a pair of victories. The first was more of a public relations boost by Gov. Larry Hogan, who rode the Yamanashi maglev on his June trip to Japan along with state Transport Secretary Pete Rahn. In a stance contrary to the usual Republican line, Hogan announced his support for the Maryland/DC maglev venture.(4)

Gov. Larry Hogan (R-MD) and wife Yumi test-ride Japan's SCMaglev. Image credit: Larry Hogan via Twitter

But Main Street's Still All Cracked and Broken

In November, TNEM scored a more substantial victory, and in the process, struck fear into millions of area residents. The group charged with project development, Baltimore Washington Rapid Rail, applied for – and received – a long-abandoned railroad franchise, which granted them the authority of eminent domain (5).

But if The Northeast Maglev expected the towns along the route to gather in song and dance in support of their venture, akin to the citizens of Springfield in the classic Simpsons episode "Marge vs. the Monorail", they were mistaken.

As the months passed and details gradually leaked out through public meetings and press releases, the maglev gained significant local opposition. Many feared that the construction process would create excessive noise, and worse, introduce more pollution than the maglev sought to eliminate in the first place. Some fail to see how it will even reduce D.C.’s infamous traffic congestion. With only three stops on the route – Baltimore, BWI Airport, and Washington – suburban traffic would be unaffected at best, as Washington's peak traffic congestion numbers take place on the roads into and out of the city.

Percentage of time spent in traffic congestion

Source: INRIX

Note: Dallas added for the sake of comparison, as its numbers are nearly identical despite having a population roughly equal to both Baltimore and Washington combined.

There was still the matter of where to build. By January of 2018, project planners narrowed the list of possible routes down to two – both of which would tunnel through swathes of Prince George’s and Anne Arundel County. The town of Greenbelt, formed as part of the New Deal in 1935, would be hit especially hard, as most of the city is covered in green space.

Soon, even town and state officials joined in on the opposition, with the city councils of Greenbelt, Laurel, and Bowie openly denouncing the project. One prominent opponent is Greenbelt city councilman Colin Byrd, who has repeatedly appeared at anti-maglev events wearing “Stop This Train” buttons. Another opponent is state delegate Jimmy Tarlau, district 47A, who believes that the state’s money is better spent on improving currently-existing public transportation.

“I think it’s a bad use of resources,” Tarlau told the Prince George's Sentinel. “We have a lot of transportation needs in Prince George’s County, and putting all this money into a high-speed line…it's just a real waste.” (6)

On October 6th, the Citizens Against This SCMaglev, together with the Greenbelt Advocates for Environmental and Social Justice, held a rally outside of Veterans Memorial Park in Bladensburg. Organizers passed out flyers and buttons, while picketers held “Stop This Train” signs toward passing cars and buses - some of whom honked their horns in a show of solidarity for the cause.

Greenbelt Advocates co-head Brian Almquist shakes hands with Greenbelt City Councilman Colin Byrd at an anti-maglev rally in Bladensburg. Image credit: Will Pitts, Greenbelt News-Review

“This is a grassroots movement. Individually, people have a very small voice, if any. So the more you can organize people...their voice becomes bigger, louder, more effective."

Greenbelt Advocates co-head Brian Almquist

Brian and Donna Almquist are the founding members of the Greenbelt Advocates, and while the group has successfully tackled other environmental issues in the town, the maglev is their highest priority at the moment.

“This is a grassroots movement,” said Mr. Almquist, in an interview for the Greenbelt News-Review. “Individually, people have a very small voice, if any. So the more you can organize people...their voice becomes bigger, louder, more effective.” (7)

In February 2019, the maglev organizers will release their next Environmental Impact Statement, which will give a clearer picture of the future of the project. With the re-election of Governor Larry Hogan in November, the maglev’s most prominent supporter will still be around to back it up.

My plane leaves in less than one minute

The Baltimore/DC Maglev project is not the only large-scale, privately financed public project designed to improve public transportation. Elon Musk's Hyperloop intends to bring riders from Los Angeles to San Francisco in 35 minutes through a combination of maglev and vaccuum technology. However, critics doubt that the project is safe, let alone feasible.

However, if Florida's new Brightline is any indication, there is a precedent for such projects succeeding. After six years of planning and construction, the first section of the line opened in 2018, offering service from Miami to West Palm Beach in 75 minutes - half the time of driving. An extension to Orlando is under construction (8). But it should be noted that the Brightline uses conventional rolling stock and diesel-electric locomotives. Not only will The Northeast Maglev have to build hundreds of miles of track and tunnel through miles of land, they must also deal with radical new technology never used before in American public transport.

Of course, there's the elephant in the room - would it really be of use to anyone?

Amtrak

Greenbelt News-Review

Brightline/Virgin Trains USA